Analysis

Somaliland as Independent State in Historic 2025 Diplomatic Breakthrough

Israel’s groundbreaking recognition of Somaliland as an independent state marks a seismic shift in Horn of Africa politics, ending 34 years of diplomatic isolation for the breakaway region.

In a diplomatic move that could reshape the geopolitical landscape of the Horn of Africa, Israel became the first nation in the world to formally recognize Somaliland on December 26, 2025. This unprecedented decision ends more than three decades of international isolation for the self-declared republic and signals a dramatic realignment in Middle Eastern and African regional politics.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced the historic agreement during a video call with Somaliland’s President Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi, positioning the recognition as an extension of the Abraham Accords framework that normalized relations between Israel and several Arab states beginning in 2020. The development arrives at a moment of heightened regional tensions and raises critical questions about sovereignty, international law, and the future of African unity.

Table of Contents

Breaking Decades of Diplomatic Isolation

Somaliland declared independence from Somalia in 1991 following a brutal civil war, but has failed to gain recognition from any United Nations member state until now. The region, which encompasses the northwestern portion of what was once British Somaliland Protectorate, has maintained effective self-governance for 34 years while building democratic institutions that contrast sharply with the instability that has plagued southern Somalia.

The timing of Israel’s recognition carries significant weight. Coming just days before Netanyahu’s scheduled December 29 meeting with U.S. President Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago, the move appears calculated to demonstrate Israel’s expanding diplomatic reach and strategic positioning in a region increasingly important for global security and trade routes.

Netanyahu said Israel would seek immediate cooperation with Somaliland in agriculture, health, technology and the economy, signaling that this partnership extends far beyond symbolic recognition. The Israeli government framed the declaration as advancing both regional peace and its capacity to monitor security threats emanating from Yemen, where Iran-backed Houthi militants have disrupted Red Sea shipping lanes.

The Abraham Accords Framework Expands to Africa

The recognition explicitly invokes the spirit of the Abraham Accords, the landmark 2020 agreements brokered during Trump’s first administration that established diplomatic relations between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan. By connecting Somaliland’s recognition to this framework, Netanyahu positions the move within a broader strategy of normalizing Israel’s relationships across the Muslim world.

The Abraham Accords were announced in August and September 2020 and signed in Washington, D.C. on September 15, 2020, mediated by the United States under President Donald Trump. These agreements represented a strategic realignment driven by shared concerns about Iran’s regional influence and opened new economic partnerships worth billions of dollars.

For Somaliland, joining the Abraham Accords offers a potential pathway to broader international recognition and economic development. President Abdullahi welcomed the agreement as a step toward regional and global peace, expressing commitment to building partnerships that promote stability across the Middle East and Africa.

Strategic Calculations Behind the Recognition

Geography drives much of the strategic logic behind this partnership. Somaliland’s location along the Gulf of Aden, directly across from Yemen, provides Israel with a strategic vantage point for monitoring Houthi activities and securing vital maritime routes through which approximately one-third of global shipping passes. The Berbera port, a major infrastructure asset in Somaliland, has already attracted significant international investment, including a $450 million development project by DP World that began in 2016.

According to Channel 12, Somaliland’s President Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi made a secret visit to Israel about two months ago, in October, meeting with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Mossad chief David Barnea and Defense Minister Israel Katz. These high-level meetings indicate the depth of planning that preceded the public announcement and suggest security cooperation forms a cornerstone of the relationship.

The economic dimensions are equally compelling. Somaliland’s economy has an estimated nominal GDP of $7.58 billion in 2024, with a per capita GDP of $1,361, representing a modest increase from 2020 levels driven by post-drought recovery in agriculture and investments in port infrastructure. While these figures reflect a developing economy, they also highlight significant potential for growth through foreign investment and technical cooperation.

Somalia’s Forceful Rejection and Regional Backlash

Somalia demanded Israel reverse its recognition of the breakaway region of Somaliland, condemning the move as an act of “aggression that will never be tolerated”. The federal government in Mogadishu immediately issued strong condemnations, describing Somaliland as an inseparable part of Somalia and vowing to pursue all diplomatic, political, and legal measures to defend its sovereignty.

The backlash extended far beyond Somalia’s borders. Regional powerhouses quickly voiced opposition to what they view as a dangerous precedent. The African Union rejected any recognition of Somaliland, reaffirming its commitment to Somalia’s territorial integrity and warning that such moves risk undermining peace and stability across the continent.

Egypt, Turkey, and Djibouti joined Somalia’s foreign minister in a coordinated diplomatic response. The Egyptian Foreign Ministry said the four countries’ top diplomats discussed how recognizing the independence of a region within a sovereign country sets a “dangerous precedent” in violation of the UN Charter. This unified stance reflects deep concerns about the implications for other separatist movements across Africa and the Middle East.

Saudi Arabia also expressed strong opposition, adding weight to the chorus of Arab states condemning the decision. The reaction underscores how Israel’s move has created fault lines that cut across traditional alliances and regional blocs.

Somaliland’s Three-Decade Journey Toward Statehood

Understanding the significance of this recognition requires examining Somaliland’s complex history. The first Somali state to be granted independence from colonial powers was Somaliland, a former British protectorate that gained independence on 26 June 1960. Just five days later, Somaliland voluntarily united with the former Italian Somalia to form the Somali Republic, driven by pan-Somali nationalist aspirations.

The union proved problematic from its inception. Northern politicians felt marginalized as political and military positions were disproportionately awarded to southerners. Tensions escalated dramatically during the brutal military dictatorship of Siad Barre, which began in 1969. Between May 1988 and March 1989, approximately 50,000 people were killed as a result of the Somalian Army’s “savage assault” on the Isaaq population in what many scholars characterize as genocide.

When Barre’s regime collapsed in January 1991, the Somali National Movement, which had led the armed resistance in the north, convened the Grand Conference of the Northern Clans in Burao. After extensive consultations amongst clan representatives and the SNM leadership, it was agreed that Northern Somalia would revoke its voluntary union with the rest of Somali Republic to form the “Republic of Somaliland” on May 18, 1991.

Since then, Somaliland has developed functioning democratic institutions that stand in stark contrast to the instability that has characterized Somalia. The region has held multiple peaceful elections, maintains its own currency, issues passports, and operates a professional military and police force. Somaliland’s 2024 electoral contest was one of only five elections in Africa that voted in an opposition party, called Waddani, and enjoyed a peaceful vote.

Economic Realities and Development Challenges

Despite its relative political stability, Somaliland faces significant economic challenges rooted primarily in its lack of international recognition. Non-recognition blocks FDI and multilateral aid, costing an estimated $1.2 billion annually in lost investments. This isolation prevents Somaliland from accessing loans from the International Monetary Fund or World Bank, severely limiting its capacity for infrastructure development.

The economy remains heavily reliant on primary sectors. Livestock exports account for approximately 70% of export earnings, contributing 60% of GDP. Remittances from the Somaliland diaspora provide crucial financial flows, with estimates suggesting roughly $1 billion reaches Somalia annually, with a substantial portion directed to Somaliland.

The government’s 2025 budget reflects the constraints of limited revenue sources. Expenditure prioritizes operational costs over development, with 58% allocated to military and civil servant salaries, 19% for utilities and maintenance, and only 23% for capital projects focusing on road repairs and education infrastructure. Critics argue this development allocation remains insufficient for addressing critical infrastructure gaps.

Youth unemployment presents another pressing challenge. Unemployment among 18-35 year-olds reaches 30%, driving migration to Europe. Climate vulnerability adds another layer of difficulty, with recurrent droughts threatening the 65% of the population that relies on pastoralism for their livelihoods.

However, there are bright spots. The Berbera port development, a joint venture with DP World and Ethiopia, represents a major infrastructure achievement that could transform Somaliland into a critical trade hub. The project, which received additional funding from the UK government’s CDC group in 2021, aims to position Berbera as a gateway for landlocked Ethiopia’s international trade.

International Law and the Recognition Debate

The legal dimensions of Somaliland’s quest for recognition involve complex questions of international law and the principle of territorial integrity. Proponents of Somaliland’s independence argue that the region has a unique case based on its distinct colonial history and the voluntary nature of its 1960 union with Somalia.

Somaliland broke ties with Somalia’s government in Mogadishu after declaring independence in 1991, and the region has sought international recognition as an independent state since then. Supporters emphasize that Somaliland meets the criteria for statehood under the 1933 Montevideo Convention: it has a defined territory, a permanent population, an effective government, and the capacity to enter into relations with other states.

Critics counter that recognizing Somaliland would violate the principle of territorial integrity enshrined in the UN Charter and the African Union’s commitment to maintaining colonial-era borders. The African Union has determined that the continent’s colonial borders should not be changed, fearing it could lead to unpredictable dynamics of secession across Africa. The exceptions of Eritrea and South Sudan occurred under special political circumstances involving agreements with the parent states.

Israel’s unilateral recognition challenges this status quo. A senior Israeli official warned that the move undermines Israel’s long-standing argument against recognizing a Palestinian state, pointing out that while Israel is the first country to grant recognition to Somaliland, the rest of the world considers the breakaway region an integral part of Somalia. This internal criticism highlights potential contradictions in Israel’s diplomatic positioning.

Trump Administration’s Ambiguous Stance

The U.S. position on Somaliland recognition remains deliberately ambiguous. While President Trump signaled interest in the issue during his first administration and again in August 2025, saying his administration was “working on” the Somaliland question, he has since distanced himself from Netanyahu’s move.

Trump told The New York Post that he would not follow Israel’s lead in recognizing Somaliland, at least not immediately. This hesitation reflects competing pressures: on one hand, influential Republican senators like Ted Cruz have advocated for Somaliland recognition; on the other, the U.S. maintains important security relationships with Somalia and seeks to avoid alienating African partners.

The Trump administration’s frustration with Somalia has been evident in recent months, with the president making critical comments about the Somali community in the United States and questioning Somalia’s commitment to security improvements despite substantial U.S. support. However, this friction has not yet translated into formal recognition of Somaliland.

Implications for Regional Security Architecture

The recognition carries profound implications for the Horn of Africa’s security landscape. Somaliland’s strategic location gives Israel a foothold in a region where Iranian influence has been expanding through proxies like the Houthi movement in Yemen. The partnership could facilitate intelligence sharing, military cooperation, and coordinated responses to threats in the Red Sea corridor.

For Somaliland, the security relationship offers access to Israeli expertise in counterterrorism, intelligence gathering, and defense technology. The region has maintained relative peace and stability compared to Somalia, with minimal terrorist activity since 2008, but it faces ongoing challenges from al-Shabaab and other extremist groups operating in neighboring territories.

However, the recognition also introduces new vulnerabilities. Somaliland could become a target for groups opposed to Israel’s regional presence. The Houthi leader Abdul Malik al-Houthi has already warned of future confrontations, framing the recognition as part of what he characterized as efforts to create divisions in Muslim nations.

Regional powers must now recalibrate their strategies. Ethiopia, which has maintained close ties with Somaliland and uses Berbera port for trade access, finds itself navigating between its economic interests and its relationships with Somalia and the Arab League. The United Arab Emirates, which invested heavily in Berbera and signed the Abraham Accords, faces questions about whether it will follow Israel’s lead.

Palestinian Displacement Controversy

Earlier this year, reports emerged linking potential recognition of Somaliland to plans for ethnically cleansing Palestinians in Gaza and forcibly moving them to the African region. These allegations have added another inflammatory dimension to an already controversial decision.

Somalia’s state minister for foreign affairs explicitly connected Israel’s recognition to alleged plans for Palestinian displacement. Critics argue that Somaliland’s geographic position and demographic space could make it attractive for such schemes, though Somaliland officials have not publicly commented on these accusations.

The controversy underscores how the Israeli-Palestinian conflict continues to influence diplomatic calculations far beyond the immediate region. For many Arab and Muslim countries, any normalization with Israel remains conditional on progress toward Palestinian statehood—a reality that has complicated the expansion of the Abraham Accords.

Economic Opportunities and Development Prospects

Beyond the geopolitical calculations, the Israel-Somaliland partnership opens significant economic possibilities. Israeli expertise in agricultural technology, water management, and renewable energy could help address some of Somaliland’s most pressing development challenges.

Israeli companies have expressed interest in telecommunications, cybersecurity, and infrastructure development. The technology transfer could accelerate Somaliland’s economic diversification away from its heavy dependence on livestock exports. Israeli agricultural innovations, particularly drought-resistant farming techniques and efficient irrigation systems, are highly relevant to Somaliland’s climate conditions.

Trade between the two countries is expected to grow substantially, though starting from a minimal base. Tourism presents another potential growth area, with Somaliland’s pristine beaches, historic sites like the Ottoman-era buildings in Zeila, and unique nomadic culture offering attractions for adventurous travelers.

The recognition could also catalyze investment from other countries seeking to establish presence in strategic locations. If the partnership proves economically beneficial, it might encourage other nations to reconsider their stance on recognition, despite the political risks.

What Comes Next: Possible Scenarios

Several possible scenarios could unfold in the coming months and years. The optimistic view suggests that Israel’s recognition could create momentum for other countries to follow, particularly if the U.S. eventually changes its position. This could trigger a cascade effect, especially among countries less concerned about African Union strictures or those seeking to balance against expanding Chinese and Russian influence in the Horn of Africa.

A more likely scenario involves cautious, incremental steps. Some countries might establish unofficial ties or representation offices without formal recognition, allowing economic engagement while avoiding direct confrontation with the AU and Somalia. Taiwan’s model of maintaining substantive relationships without formal recognition could provide a template.

The pessimistic scenario envisions increased regional instability. Somalia could escalate diplomatic and potentially military pressure on Somaliland, particularly in contested border regions. The recognition could also trigger copycat independence movements elsewhere in Africa, validating AU concerns about opening Pandora’s box.

Much depends on how effectively Somaliland manages this opportunity. Building on the recognition to demonstrate good governance, economic development, and regional cooperation could strengthen its case for broader acceptance. Conversely, any internal instability or regional conflicts could undermine its claims to effective statehood.

Expert Perspectives on Long-Term Impact

International relations scholars offer divergent assessments of this development’s significance. Some argue that Israel’s recognition represents a fundamental shift in how the international community approaches self-determination and recognition, potentially establishing precedent for other de facto states worldwide.

Others contend that the move reflects opportunistic realpolitik rather than principled support for self-determination. They note that Israel’s recognition serves its strategic interests while creating complications for its diplomatic arguments regarding Palestinian statehood.

Key Takeaways

- Israel’s December 26, 2025 recognition of Somaliland ends 34 years without any international recognition

- The move is framed within the Abraham Accords framework established in 2020

- Somalia, the African Union, and multiple Arab states strongly oppose the recognition

- Strategic calculations include monitoring Yemen, securing Red Sea trade routes, and economic cooperation

- Somaliland has maintained democratic governance and relative stability since 1991

- Economic challenges persist due to international isolation, with $1.2 billion in annual lost investment

- The U.S. position remains ambiguous despite President Trump’s past interest

- Regional security implications are significant given proximity to Yemen and Houthi activities

- The recognition raises questions about self-determination, territorial integrity, and international law

- Future developments depend on reactions from other nations and the sustainability of the Israel-Somaliland partnership

Regional security analysts emphasize the military and intelligence dimensions. They predict that the partnership will deepen significantly in these areas, potentially including Israeli military training, equipment sales, and shared intelligence operations targeting mutual threats. The proximity to Yemen makes Somaliland valuable for monitoring and potentially intercepting weapons shipments to Houthi forces.

Development economists focus on whether recognition translates into meaningful economic benefits for Somaliland’s population. They caution that without access to international financial institutions and multilateral development banks, the economic impact may remain limited despite bilateral cooperation with Israel.

Conclusion: A Watershed Moment with Uncertain Future

Israel’s recognition of Somaliland marks an undeniable watershed moment in Horn of Africa geopolitics. After 34 years of international isolation, Somaliland has secured its first formal recognition from a UN member state, fundamentally altering the region’s diplomatic landscape.

The partnership brings together two entities seeking to expand their international standing through strategic alignment. For Israel, it represents expanded reach in a critical region and another diplomatic victory in its campaign to normalize relations across the Muslim world. For Somaliland, it offers long-sought validation of its independence claims and potential pathways to economic development and international engagement.

However, significant obstacles and uncertainties remain. The fierce opposition from Somalia, the African Union, and much of the Arab world creates a hostile environment for expanding recognition. The controversy over Palestinian displacement allegations adds moral complexity to what proponents frame as a straightforward matter of respecting self-determination.

The coming months will reveal whether this recognition represents the beginning of broader international acceptance for Somaliland or an isolated diplomatic anomaly. Netanyahu’s meeting with Trump will provide crucial signals about U.S. intentions. The reactions of other Abraham Accords signatories—particularly the UAE—will indicate whether additional countries might follow Israel’s lead.

What remains certain is that December 26, 2025, will be remembered as a historic date in Somaliland’s quest for statehood. Whether it marks the beginning of genuine independence or simply a new chapter in its long diplomatic struggle depends on how the international community responds to this unprecedented development.

For the millions of Somalilanders who have lived in a state of diplomatic limbo since 1991, Israel’s recognition offers hope—tempered by the awareness that the path to full international acceptance remains long and fraught with challenges. As President Abdullahi navigates this new reality, he must balance the opportunities this partnership presents against the risks of further regional isolation and the need to maintain Somaliland’s hard-won stability.

The story of Somaliland’s recognition is still being written, and its final chapter remains uncertain.

Discover more from The Monitor

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

Pakistan’s Humiliating Defeat to India: A Catalog of Captaincy Failures at T20 World Cup 2026

India’s 61-run demolition of Pakistan in Colombo exposes systematic flaws in team selection, tactical nous, and leadership under Salman Agha

When Salman Agha won the toss and elected to bowl first under the Colombo floodlights on Sunday evening, few could have predicted the scale of Pakistan’s capitulation that would follow. India’s comprehensive 61-run victory—their eighth win in nine T20 World Cup encounters against their arch-rivals—was not merely a defeat. It was an autopsy of Pakistan cricket’s endemic problems: mystifying team selections, baffling tactical decisions, and a captaincy that appears chronically underprepared for the intensity of India-Pakistan clashes.

The scoreline tells part of the story. India posted 175/7 in their 20 overs, with Ishan Kishan’s blistering 77 off 40 balls serving as the cornerstone. In response, Pakistan crumbled to 114 all out in just 18 overs, their batting lineup disintegrating like a sandcastle before the tide. But the numbers alone cannot capture the deeper malaise—the inexplicable decision-making that has become a hallmark of Pakistan’s recent tournament play.

Table of Contents

The Toss That Lost the Match

Salman Agha won the toss and decided to bowl first on what he described as a “tacky” surface, believing it would assist bowlers in the early overs. The logic appeared sound on paper: exploit early movement, restrict India to a manageable total, and chase under lights as the pitch improved. India’s captain Suryakumar Yadav, by contrast, indicated they would have batted first anyway, expecting the pitch to slow down enough to counter any dew advantage later.

The decision proved catastrophic. On spin-friendly Colombo tracks that historically become harder to bat on as matches progress, Pakistan handed India first use of the surface. As events unfolded, 175 became the highest score in India-Pakistan T20 World Cup history—hardly the restricted total Agha had envisioned. Worse, when Pakistan batted, the pitch offered turn and variable bounce that rendered strokeplay treacherous.

The toss decision encapsulated a broader failure of match awareness. Senior analysts on ESPN Cricinfo noted that if pitches are tacky to begin with, they tend to get better as temperatures drop at night—precisely the opposite of Agha’s reasoning. This fundamental misreading of conditions set the tone for what followed.

The Selection Mysteries: Fakhar, Naseem, and Nafay

Perhaps nothing better illustrates Pakistan’s rudderless approach than the team selection. Three players with proven credentials against India—or specific skills suited to Colombo conditions—were inexplicably relegated to the bench.

Fakhar Zaman, one of Pakistan’s most destructive limited-overs batsmen, watched from the sidelines despite his storied history against India. Fakhar has played 117 T20Is, scoring 2,385 runs at a strike rate of 130.75, and his 2017 Champions Trophy century against India remains one of Pakistan cricket’s defining moments. His aggressive batting style and ability to play pace and spin with equal fluency made him an obvious selection for the high-pressure cauldron of an India clash. Yet the team management persisted with Babar Azam at number four—a batsman who managed just 5 runs off 7 balls before being bowled by Axar Patel and whose recent form against India has been woeful.

Naseem Shah, the young pace sensation who has repeatedly demonstrated his ability to extract bounce and movement even from docile surfaces, was another puzzling omission. While Pakistan’s squad featured Naseem as a key pace option alongside Shaheen Shah Afridi, the playing XI instead deployed Faheem Ashraf—a bowler whose international returns have been modest at best. Naseem’s pace and ability to hit the deck hard would have provided the ideal counterpoint to India’s aggressive openers, particularly on a pitch offering assistance to quicker bowlers in the early overs.

Khawaja Nafay, named in the 15-man squad as a wicketkeeper-batsman option, similarly failed to make the cut. His exclusion was particularly glaring given Pakistan’s top-order fragility and the presence of two specialist wicketkeepers (Usman Khan and Sahibzada Farhan) in the lineup already.

The cumulative effect was a team that looked ill-equipped for the challenge, lacking both firepower and balance.

Spinner Overload: Too Many Cooks

If the batting order selections raised eyebrows, Pakistan’s bowling composition bordered on the incomprehensible. The team fielded a staggering array of spin options: Saim Ayub (part-time left-arm orthodox), Abrar Ahmed (leg-spinner/googly specialist), Shadab Khan (leg-spinner), Mohammad Nawaz (left-arm orthodox), Usman Tariq (mystery spinner), and captain Salman Agha himself (off-spinner).

Six spin options in a T20 match. The redundancy was staggering.

To make matters worse, Pakistan bowled five overs of spin in the powerplay alone—only the 13th time in T20 World Cup history that a fifth spin over has been bowled inside a powerplay. While the Colombo surface offered turn, this approach played directly into India’s hands. Kishan, a devastatingly effective player of spin, feasted on the lack of variety. Shadab Khan, Abrar Ahmed, and Shaheen Shah Afridi combined to concede 86 runs in six overs—a hemorrhaging of runs that effectively ended the contest as a spectacle.

The tactical poverty was evident in specific passages of play. Pakistan bowled Shadab Khan to two left-handed batters and brought Abrar Ahmed back despite him having a “stinker” of a night. In the death overs, rather than employing spin to squeeze India, Shaheen Shah Afridi was brought back for the final over and plundered for 16 runs, allowing India to surge past 175.

The spinner overload wasn’t merely a tactical misstep—it revealed a captain uncertain of his resources and unwilling to commit to a coherent plan.

The Batting Order Blunder: Agha Before Babar

Among the more peculiar decisions was the batting order itself. Salman Agha, the captain and an all-rounder by trade, was promoted to number three—ahead of Babar Azam, Pakistan’s most accomplished batsman.Even players like Mohammad Haris , Mohammad Rizwan ,Minhas were not picked for the squad , It is big blunder made by Aquib Javed and others who slected the squad . Pakistan team did not select the aggressive players like Abdul Samad and already wasted talented Asif Ali and Irfan Khan Niazi . There was none who could hit six to shift the pressure and speed up momentum . The chequred history of defeats against India in world cup still hounds and same happened today .Will anybody take the responsibility of poor selection and worst captaincy to step down and fix the issues . Even the smaller and new teams like,Afghanistan ,USA , Italy , Zimbabwe performed well and gave tough time to opponents . When will they learn the lesson . They prove to be a wall of Sand against India in world cup encounters disappointed and hurting the feelinhs and dreams of the fans .

The rationale is unclear. Agha’s T20 record is respectable but hardly stellar; his primary value lies in his ability to bowl tidy off-spin and provide lower-order impetus. Elevating him above Babar—who, despite recent struggles, remains Pakistan’s premier accumulator—suggested either a crisis of confidence in Babar or a fundamental misunderstanding of optimal batting orders.

When Pakistan’s chase began, the decision’s folly became immediately apparent. Hardik Pandya dismissed Sahibzada Farhan for a duck in his first over, and Jasprit Bumrah then removed both Saim Ayub and Salman Agha in quick succession. Pakistan found themselves at 13 for 3 within two overs, with their captain having contributed a meager 4 runs. Babar entered at the fall of the third wicket and lasted just 16 balls before departing for 5, caught between the need for consolidation and the mounting run rate.

The structural flaw was glaring: by promoting Agha, Pakistan had effectively wasted a top-order slot. Had Babar batted at three or as opener—his natural positions—he might have anchored the innings through the powerplay carnage. Instead, Pakistan’s best batsman arrived with the game already slipping away, the asking rate climbing, and pressure mounting exponentially.Pakistan failed to dominate both the pace and Spin attack of India .

Kishan’s Masterclass and India’s Clinical Execution

To credit Pakistan’s failings alone would be to diminish India’s superlative performance. Ishan Kishan’s 77 off 40 balls, featuring 10 fours and 3 sixes, set the template for an innings of controlled aggression. Kishan’s ability to dominate Pakistan’s spin-heavy attack—particularly his audacious strokeplay against Abrar Ahmed and Mohammad Nawaz—showcased the chasm in class and preparation between the two sides.

Captain Suryakumar Yadav contributed 32 off 29 balls, while Shivam Dube’s 27 off 17 deliveries and Tilak Varma’s 25 off 24 balls provided crucial support. India’s depth allowed them to absorb the twin blows of Abhishek Sharma’s early dismissal and Hardik Pandya’s duck, building partnerships and accelerating at will.

With the ball, India were relentless. Hardik Pandya and Jasprit Bumrah shared three early wickets, reducing Pakistan to 38/4 at the end of the powerplay. Axar Patel claimed two crucial scalps, including Babar Azam, while Varun Chakaravarthy’s 2 for 17 included back-to-back dismissals of Faheem Ashraf and Abrar Ahmed. The variety and precision of India’s attack—three seamers, three spinners, all delivering match-winning spells—stood in stark contrast to Pakistan’s scattergun approach.

A Pattern of Captaincy Failures

Salman Agha’s tenure as Pakistan captain has been brief, but the India match crystallized a troubling pattern. This was not an isolated aberration but rather symptomatic of deeper issues within Pakistan cricket: reactive rather than proactive thinking, selection driven by sentiment rather than form, and tactical naivety at crucial junctures.

Former Pakistan cricketers have been scathing. Ahead of the match, Rashid Latif, Mohammad Amir, and Ahmed Shehzad openly questioned Babar’s continued place in the team, highlighting concerns about his strike rate and diminishing returns in high-pressure games. Their prophecies proved prescient: Babar’s failure was emblematic of a team trapped between nostalgia for past glories and the brutal demands of modern T20 cricket.

The Pakistan Cricket Board’s instability has not helped. Frequent changes in leadership, coaching staff, and selection philosophy have created an environment where mediocrity is tolerated and accountability is scarce. This instability trickles down to team selection and on-field strategy, producing the kind of rudderless performance witnessed in Colombo.

What Now for Pakistan?

Pakistan’s path to the Super Eight stage remains viable but fraught with peril. They must now beat Namibia in their final group game to secure progression, a task that should be straightforward but, given recent form, carries no guarantees.

Beyond results, however, Pakistan faces deeper questions. Can Salman Agha learn from this debacle and impose a coherent tactical identity? Will the selectors have the courage to drop underperforming big names like Babar in favor of form players like Fakhar? And can the PCB provide the stability necessary for long-term planning rather than lurching from crisis to crisis?

The answers will define not only this tournament but Pakistan cricket’s trajectory for years to come. For now, the evidence suggests a team—and a system—in disarray.

Key Takeaways

- Toss Blunder: Pakistan’s decision to bowl first on a pitch that would deteriorate backfired spectacularly

- Selection Errors: Fakhar Zaman, Naseem Shah, and Khawaja Nafay inexplicably benched despite strong credentials

- Spinner Overload: Six spin options diluted Pakistan’s bowling attack, allowing India to dominate

- Batting Order Chaos: Salman Agha promoted above Babar Azam defied logic and wasted a top-order slot

- Systemic Issues: PCB instability and lack of accountability continue to undermine team performance

Match Summary:

India 175/7 (20 overs) – Ishan Kishan 77 (40), Suryakumar Yadav 32 (29); Saim Ayub 3/25

Pakistan 114 (18 overs) – Usman Khan 44 (34); Hardik Pandya 2/16, Jasprit Bumrah 2/17, Varun Chakaravarthy 2/17

Result: India won by 61 runs

About the Match: The encounter at R. Premadasa Stadium marked India’s eighth win over Pakistan in nine T20 World Cup meetings, reinforcing their psychological dominance in cricket’s most-watched rivalry. The result secured India’s passage to the Super Eight stage while leaving Pakistan’s campaign hanging by a thread.

Discover more from The Monitor

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

The Kashmir Conflict and the Reality of Crimes Against Humanity

Crimes against humanity represent one of the most serious affronts to human dignity and collective conscience. They embody patterns of widespread or systematic violence directed against civilian populations — including murder, enforced disappearances, torture, persecution, sexual violence, deportation, and other inhumane acts that shock the moral order of humanity. The United Nations Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime against Humanity presents a historic opportunity to strengthen global resolve, reinforce legal frameworks, and advance cooperation among states to ensure accountability, justice, and meaningful prevention.

While the international legal architecture has evolved significantly since the aftermath of the Second World War, important normative and institutional gaps remain. The Genocide Convention of 1948 and the Geneva Conventions established foundational legal protections, and the creation of the International Criminal Court reinforced accountability mechanisms. Yet, unlike genocide and war crimes, there is still no stand-alone comprehensive convention dedicated exclusively to crimes against humanity. This structural omission has limited the capacity of states to adopt consistent domestic legislation, harmonize cooperation frameworks, and pursue perpetrators who move across borders. The Conference of Plenipotentiaries seeks to fill this critical void.

The Imperative of Prevention

Prevention must stand at the core of the international community’s approach. Too often, the world reacts to atrocities only after irreparable harm has been inflicted and communities have been devastated. A meaningful prevention framework requires early warning mechanisms, stronger monitoring capacities, transparent reporting, and a willingness by states and institutions to act before crises escalate. Education in human rights, inclusive governance, rule of law strengthening, and responsible security practices are equally essential elements of prevention.

Civil society organizations, academic institutions, moral leaders, and human rights defenders play a vital role in documenting abuses, amplifying the voices of victims, and urging action when warning signs emerge. Their protection and meaningful participation must therefore be an integral component of any preventive strategy. Without civic space, truth is silenced — and without truth, accountability becomes impossible.

Accountability and the Rule of Law

Accountability is not an act of punishment alone; it is an affirmation of universal human values. When perpetrators enjoy impunity, cycles of violence deepen, victims are re-traumatized, and the integrity of international law erodes. Strengthening judicial cooperation — including extradition, mutual legal assistance, and evidence-sharing — is essential to closing enforcement gaps. Equally important is the responsibility of states to incorporate crimes against humanity into domestic criminal law, ensuring that such crimes can be prosecuted fairly and independently at the national level.

Justice must also be survivor centered. Victims and affected communities deserve recognition, reparations, psychological support, and the assurance that their suffering has not been ignored. Truth-seeking mechanisms and memorialization efforts help restore dignity and foster long-term reconciliation.

The Role of Multilateralism

The Conference reinforces the indispensable role of multilateralism in confronting global challenges. Atrocities rarely occur in isolation; they are rooted in political exclusion, discrimination, securitization of societies, and structural inequalities. No state, however powerful, can confront these dynamics alone. Shared norms, coordinated diplomatic engagement, and principled international cooperation are vital to preventing abuses and responding when they occur.

Multilateral commitments must also be matched with political will. Declarations are meaningful only when accompanied by implementation, transparency, and accountability to both domestic and international publics.

Technology, Media, and Modern Challenges

Contemporary conflicts and crises unfold in an increasingly digital and interconnected world. Technology can illuminate truth — enabling documentation, verification, and preservation of evidence — but it can also be weaponized to spread hate, dehumanization, and incitement. Strengthening responsible digital governance, countering disinformation, and supporting credible documentation initiatives are essential tools for both prevention and accountability. Journalists, researchers, and human rights monitors must be protected from reprisals for their work.

Climate-related stress, demographic shifts, and political polarization further complicate the landscape in which vulnerabilities emerge. The Conference should therefore promote a holistic understanding of risk factors that may precipitate widespread or systematic violence.

A Universal Commitment — With Local Realities

While the principles guiding this Convention are universal, their application must be sensitive to local histories, languages, cultures, and institutional realities. Effective implementation depends on national ownership, capacity-building, judicial training, and inclusive policymaking that engages women, youth, minorities, and marginalized communities. The pursuit of justice must never be perceived as externally imposed, but rather as an expression of shared human values anchored within domestic legal systems.

The Kashmir Conflict and the Reality of Crimes Against Humanity

Crimes against humanity do not emerge overnight. They develop through sustained patterns of abuse, erosion of legal safeguards, and the normalization of repression. Jammu and Kashmir presents a contemporary case study of these dynamics.

Under international law, crimes against humanity encompass widespread or systematic attacks directed against a civilian population, including imprisonment, torture, persecution, enforced disappearance, and other inhumane acts. Evidence emerging from Kashmir—documented by UN experts, international NGOs, journalists, and scholars—demonstrates patterns that meet these legal criteria.

The invocation of “national security” has become the central mechanism through which extraordinary powers are exercised without effective judicial oversight. Draconian laws are routinely used to silence dissent, detain human rights defenders, restrict movement, and suppress independent media. This securitized governance has produced what many Kashmiris describe as the “peace of the graveyard”—an imposed silence rather than genuine peace.

Early-warning frameworks for mass atrocities are particularly instructive. Gregory Stanton identifies Kashmir as exhibiting multiple risk indicators, including classification and discrimination, denial of civil rights, militarization, and impunity. These indicators, if left unaddressed, historically precede mass atrocity crimes.

The systematic silencing of journalists, as warned by the Committee to Protect Journalists, and the targeting of academics and diaspora voices—such as the denial of entry to Dr. Nitasha Kaul and the cancellation of travel documents of elderly activists like Amrit Wilson—demonstrate repression extending beyond borders.

The joint statement by ten UN Special Rapporteurs (2025) regarding one of internationally known human rights defender – Khurram Parvez – underscores that these are not isolated incidents but part of a broader pattern involving arbitrary detention, torture, discriminatory treatment, and custodial deaths. Together, these acts form a systematic attack on a civilian population, triggering the international community’s responsibility to act.

This Conference offers a critical opportunity to reaffirm that sovereignty cannot be a shield for crimes against humanity. Kashmir illustrates the urgent need for:

- Preventive diplomacy grounded in early warning mechanisms.

- Independent investigations and universal jurisdiction where applicable.

- Stronger protections for journalists, scholars, and human rights defenders, including Irfan Mehraj, Abdul Aaala Fazili, Hilal Mir, Asif Sultan and others.

- Victim-centered justice and accountability frameworks for Mohammad Yasin Malik, Shabir Ahmed Shah, Masarat Aalam, Aasia Andrabi, Fehmeeda Sofi, Nahida Nasreen and others.

Recognizing Kashmir within the crimes-against-humanity discourse is not political—it is legal, moral, and preventive. Failure to act risks entrenching impunity and undermining the very purpose of international criminal law.

Conclusion

The United Nations Conference of Plenipotentiaries carries profound moral, legal, and historical significance. It represents not only a technical exercise in treaty development but a reaffirmation of humanity’s collective promise — that no people, anywhere, should face systematic cruelty without recourse to justice and protection. By advancing a comprehensive Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime against Humanity, the international community strengthens its resolve to stand with victims, confront impunity, and uphold the sanctity of human dignity.

The success of this effort will ultimately depend on our willingness to transform commitments into action, principles into practice, and aspiration into enduring protection for present and future generations.

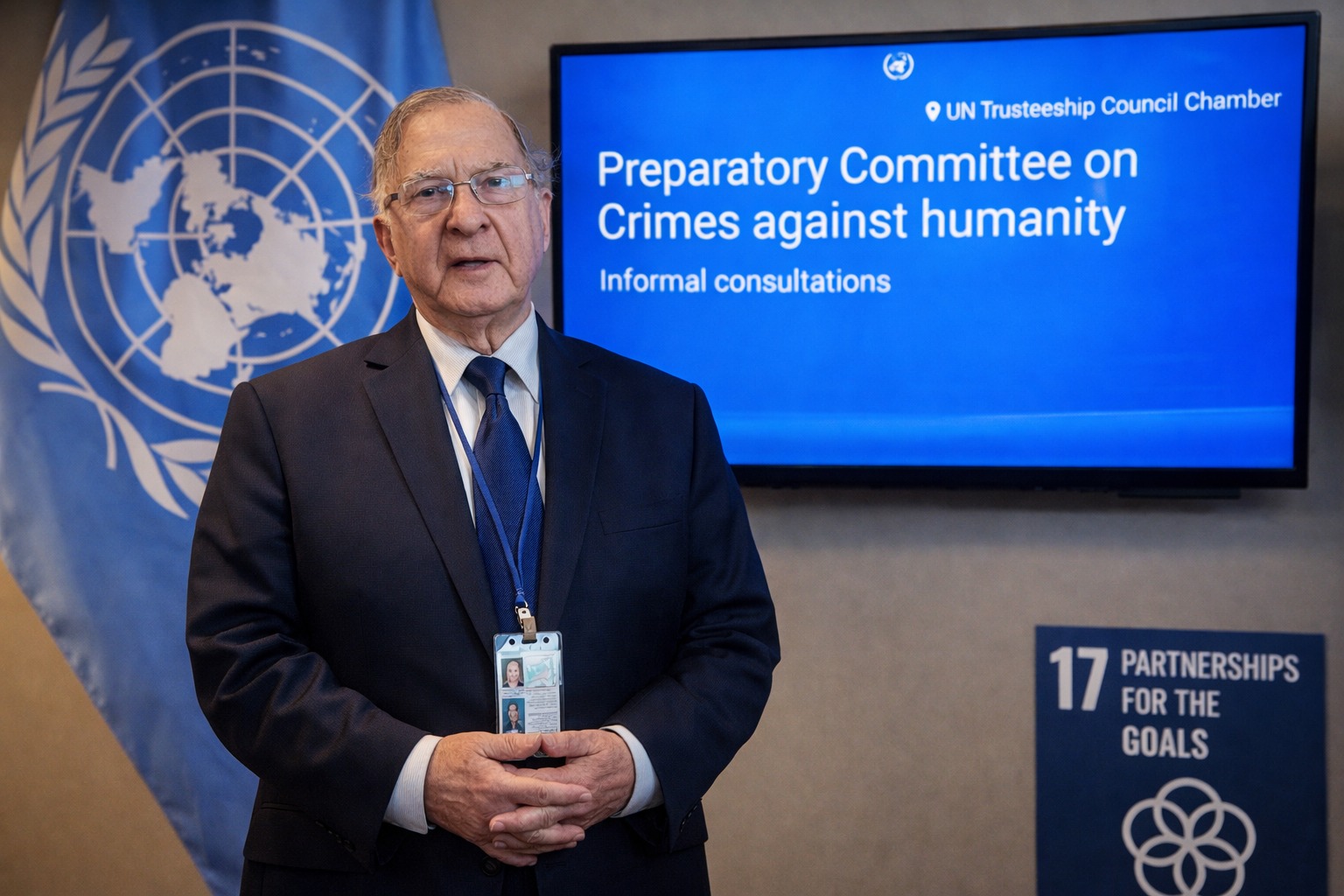

Dr. Fai submitted this paper to the Organizers of the Preparatory Committee for the United Nations Conference of Plenipotentiaries on Prevention and Punishment of Crimes against Humanity on behalf of PCSWHR which is headed by Dr. Ijaz Noori, an internationally known interfaith expert. The conference took place at the UN headquarters between January 19 – 30, 2026.

Discover more from The Monitor

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

What Is Nipah Virus? Symptoms, Risks, and Transmission Explained as India Faces New Outbreak Alert

KOLKATA, West Bengal—In the intensive care unit of a Kolkata hospital, shielded behind layers of protective glass, a team of healthcare workers moves with a calibrated urgency. Their patient, a man in his forties, is battling an adversary they cannot see and for which they have no specific cure. He is one of at least five confirmed cases in a new Nipah virus outbreak in West Bengal, a stark reminder that the shadow of zoonotic pandemics is long, persistent, and profoundly personal. Among the cases are two frontline workers, a testament to the virus’s stealthy human-to-human transmission. Nearly 100 contacts now wait in monitored quarantine, their lives paused as public health officials race to contain a pathogen with a terrifying fatality rate of 40 to 75 percent.

This scene in India is not from a dystopian novel; it is the latest chapter in a two-decade struggle against a virus that emerges from forests, carried by fruit bats, to sporadically ignite human suffering. As of January 27, 2026, containment efforts are underway, but the alert status remains high. There is no Nipah virus vaccine, no licensed antiviral. Survival hinges on supportive care, epidemiological grit, and the hard-learned lessons from past outbreaks in Kerala and Bangladesh.

For a global audience weary of pandemic headlines, the name “Nipah” may elicit a flicker of recognition. But what is Nipah virus, and why does its appearance cause such profound concern among virologists and public health agencies worldwide? Beyond the immediate crisis in West Bengal, this outbreak illuminates the fragile interplay between a changing environment, animal reservoirs, and human health—a dynamic fueling the age of emerging infectious diseases.

Table of Contents

Understanding the Nipah Virus: A Zoonotic Origin Story

Nipah virus (NiV) is not a newcomer. It is a paramyxovirus, in the same family as measles and mumps, but with a deadlier disposition. It was first identified in 1999 during an outbreak among pig farmers in Sungai Nipah, Malaysia. The transmission chain was traced back to fruit bats of the Pteropus genus—the virus’s natural reservoir—who dropped partially eaten fruit into pig pens. The pigs became amplifying hosts, and from them, the virus jumped to humans.

The South Asian strain, however, revealed a more direct and dangerous pathway. In annual outbreaks in Bangladesh and parts of India, humans contract the virus primarily through consuming raw date palm sap contaminated by bat urine or saliva. From there, it gains the ability for efficient human-to-human transmission through close contact with respiratory droplets or bodily fluids, often in家庭or hospital settings. This capacity for person-to-person spread places it in a category of concern distinct from many other zoonoses.

“Nipah sits at a dangerous intersection,” explains a virologist with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Emerging Diseases unit. “It has a high mutation rate, a high fatality rate, and proven ability to spread between people. While its outbreaks have so far been sporadic and localized, each event is an opportunity for the virus to better adapt to human hosts.” The WHO lists Nipah as a priority pathogen for research and development, alongside Ebola and SARS-CoV-2.

Key Symptoms and Progression: From Fever to Encephalitis

The symptoms of Nipah virus infection can be deceptively nonspecific at first, often leading to critical delays in diagnosis and isolation. The incubation period ranges from 4 to 14 days. The illness typically progresses in two phases:

- Initial Phase: Patients present with flu-like symptoms including:

- High fever

- Severe headache

- Muscle pain (myalgia)

- Vomiting and sore throat

- Neurological Phase: Within 24-48 hours, the infection can progress to acute encephalitis (brain inflammation). Signs of this dangerous progression include:

- Dizziness, drowsiness, and altered consciousness.

- Acute confusion or disorientation.

- Seizures.

- Atypical pneumonia and severe respiratory distress.

- In severe cases, coma within 48 hours.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the case fatality rate is estimated at 40% to 75%, a staggering figure that varies by outbreak and local healthcare capacity. Survivors of severe encephalitis are often left with long-term neurological conditions, such as seizure disorders and personality changes.

Transmission Routes and Risk Factors

Understanding Nipah virus transmission is key to breaking its chain. The routes are specific but expose critical vulnerabilities in our food systems and healthcare protocols.

- Zoonotic (Animal-to-Human): The primary route. The consumption of raw date palm sap or fruit contaminated by infected bats is the major risk factor in Bangladesh and India. Direct contact with infected bats or their excrement is also a risk. Interestingly, while pigs were the intermediate host in Malaysia, they have not played a role in South Asian outbreaks.

- Human-to-Human: This is the driver of hospital-based and家庭clusters. The virus spreads through:

- Direct contact with respiratory droplets (coughing, sneezing) from an infected person.

- Contact with bodily fluids (saliva, urine, blood) of an infected person.

- Contact with contaminated surfaces in clinical or care settings.

This mode of transmission makes healthcare workers exceptionally vulnerable, as seen in the current West Bengal cases and the devastating 2018 Kerala outbreak, where a nurse lost her life after treating an index patient. The lack of early, specific symptoms means Nipah can enter a hospital disguised as a common fever.

The Current Outbreak in West Bengal: Containment Under Pressure

The Nipah virus India 2026 outbreak is centered in West Bengal, with confirmed cases receiving treatment in Kolkata-area hospitals. As reported by NDTV, state health authorities have confirmed at least five cases, including healthcare workers, with one patient in critical condition. The swift response includes:

- The quarantine and daily monitoring of nearly 100 high-risk contacts.

- Isolation wards established in designated hospitals.

- Enhanced surveillance in the affected districts.

- Public advisories against consuming raw date palm sap.

This outbreak echoes, but is geographically distinct from, the several deadly encounters Kerala has had with the virus, most notably in 2018 and 2023. Each outbreak tests India’s increasingly robust—yet uneven—infectious disease response infrastructure. The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and the National Institute of Virology (NIV) have deployed teams and are supporting rapid testing, which is crucial for containment.

Airports in the region, recalling measures from previous health crises, have reportedly instituted thermal screening for passengers from affected areas, a move aimed more at public reassurance than efficacy, given Nipah’s incubation period.

Why the Fatality Rate Is So High: A Perfect Storm of Factors

The alarming Nipah virus fatality rate is a product of biological, clinical, and systemic factors:

- Neurotropism: The virus has a strong affinity for neural tissue, leading to rapid and often irreversible brain inflammation.

- Lack of Specific Treatment: There is no vaccine for Nipah virus and no licensed antiviral therapy. Treatment is purely supportive: managing fever, ensuring hydration, treating seizures, and, in severe cases, mechanical ventilation. Monoclonal antibodies are under development and have been used compassionately in past outbreaks, but they are not widely available.

- Diagnostic Delays: Early symptoms mimic common illnesses. Without rapid, point-of-care diagnostics, critical isolation and care protocols are delayed, increasing the opportunity for spread and disease progression.

- Healthcare-Associated Transmission: Outbreaks can overwhelm infection prevention controls in hospitals, turning healthcare facilities into amplification points, which increases the overall case count and mortality.

Global Implications and Preparedness

While the current Nipah virus outbreak is a local crisis, its implications are global. In an interconnected world, no outbreak is truly isolated. The World Health Organization stresses that Nipah epidemics can cause severe disease and death in humans, posing a significant public health concern.

Furthermore, Nipah is a paradigm for a larger threat. Habitat loss and climate change are bringing wildlife and humans into more frequent contact. The Pteropus bat’s range is vast, spanning from the Gulf through the Indian subcontinent to Southeast Asia and Australia. Urbanization and agricultural expansion increase the odds of spillover events.

“The story of Nipah is the story of our time,” notes a global health security analyst in a piece for SCMP. “It’s a virus that exists in nature, held in check by ecological balance. When we disrupt that balance through deforestation, intensive farming, or climate stress, we roll the dice on spillover. West Bengal today could be somewhere else tomorrow.”

International preparedness is patchy. High-income countries have sophisticated biosecurity labs but may lack experience with the virus. Countries in the endemic region have hard-earned field experience but often lack resources. Bridging this gap through data sharing, capacity building, and joint research is essential.

Prevention and Future Outlook

Until a Nipah virus vaccine becomes a reality, prevention hinges on public awareness, robust surveillance, and classical public health measures:

- Community Education: In endemic areas, public campaigns must clearly communicate the dangers of consuming raw date palm sap and advise covering sap collection pots to prevent bat access.

- Enhanced Surveillance: Implementing a “One Health” approach that integrates human, animal, and environmental health monitoring to detect spillover events early.

- Hospital Readiness: Ensuring healthcare facilities in at-risk regions have protocols for rapid identification, isolation, and infection control, and that workers have adequate personal protective equipment (PPE).

- Accelerating Research: The pandemic has shown the world the value of platform technologies for vaccines. Several Nipah virus vaccine candidates are in various trial stages, supported by initiatives like the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI). Similarly, research into antiviral treatments like remdesivir and monoclonal antibodies must be prioritized.

The future outlook is one of cautious vigilance. Eradicating Nipah is impossible—its reservoir is wild, winged, and widespread. The goal is effective management: early detection, swift containment, and reducing the case fatality rate through better care and, eventually, medical countermeasures.

Conclusion: A Test of Vigilance and Cooperation

The patients in Kolkata’s isolation wards are more than statistics; they are a poignant call to action. The Nipah virus India outbreak in West Bengal is a flare in the night, illuminating the persistent vulnerabilities in our global health defenses. It reminds us that while COVID-19 may have redefined our scale of concern, it did not invent the underlying risks.

Nipah’s high fatality rate and capacity for human-to-human transmission demand respect, but not panic. The response in West Bengal demonstrates that with swift action, contact tracing, and community engagement, chains of transmission can be broken, even without a magic bullet cure.

Ultimately, the narrative of Nipah is not solely one of threat, but of trajectory. It shows where we have been—reactive, often scrambling. And it points to where we must go: toward a proactive, collaborative, and equitable system of pandemic preparedness. This means investing in research for neglected pathogens, strengthening health systems at the grassroots, and respecting the delicate ecological balances that, when disturbed, send silent passengers from the forest into our midst. The goal is not just to contain the outbreak of today, but to build a world resilient to the viruses of tomorrow.

Discover more from The Monitor

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

-

Featured5 years ago

Featured5 years agoThe Right-Wing Politics in United States & The Capitol Hill Mayhem

-

News4 years ago

News4 years agoPrioritizing health & education most effective way to improve socio-economic status: President

-

China5 years ago

China5 years agoCoronavirus Pandemic and Global Response

-

Canada5 years ago

Canada5 years agoSocio-Economic Implications of Canadian Border Closure With U.S

-

Democracy5 years ago

Democracy5 years agoMissing You! SPSC

-

Conflict5 years ago

Conflict5 years agoKashmir Lockdown, UNGA & Thereafter

-

Democracy5 years ago

Democracy5 years agoPresident Dr Arif Alvi Confers Civil Awards on Independence Day

-

Digital5 years ago

Digital5 years agoPakistan Moves Closer to Train One Million Youth with Digital Skills